The Project

Digital Mythology and Arabic Literature:

A Digital Archive to Study the Dynamics of the Reception

of Greek Myths in Modern Arabic Literature

The reception of the Greek classics and mythology in modern Arabic literature is part of the process of cultural interaction between Europe and the Arab world that, since 19th century, represented one of the engines of the cultural renaissance wave known as nahḍah. This cultural interaction represents an extremely interesting field of study, as it demonstrates how the Arab case is quite distant from the assimilation, differentiation or exile strategies from a dominant literary space that Pascale Casanova (2004: 175-204) envisages for small literatures or literary deprived territories. While it is true that at the turn of the 19th century the Arab world was in a state of great political and technological weakness if compared to the European States, the historical importance of its culture meant that this interaction was quite similar to the processes of partial assimilation and cultural borrowing described by Fred Dallmayr (1996: 18). These processes occur when cultures face each other on a more nearly equal or roughly comparable basis, resulting in phenomena of incorporation, syncretism or a movement of genuine self-transformation. The modern Arab interest in ancient Greek literature grew within this framework of interactions. This interest was stimulated both by the rampant “Hellenomania” of those years in Europe (Bernal 1987: 281-336), and by the fact that the reception of the classics was deemed as a condition to be part of world literature (Noorani 2019: 236-265). At the same time, the very assimilation of the category of “classics” led to the revivification of the Arab heritage, which included the translation and the re-elaboration of Greek knowledge chiefly during the Abbasid rule. However, in an unprecedented way compared to this medieval transmission, which had privileged philosophy and the sciences over other fields of study, Arab modernity was finally exposed to Greek literary production and, consequently, to its mythical heritage.

A vast literature has analysed the transmission of Greek knowledge to Arab culture. Most of this literature refers specifically to the Greek influence on Arab sciences and philosophy during the first centuries of Arab-Islamic history, with few references to literature (Rosenthal 1992; Gutas 1998; Capezzone 1998; Strohmeier 2003). A specific attention to literature is in Malāmiḥ yūnāniyyah fī l-adab al-ʿarabī (Greek aspects in Arabic literature) by Iḥsān ʿAbbās (1977), who retraces the medieval reception of Greek wisdom literature and of Greek authors such as Homer or Aesop. Homer certainly had great success in the scholarly literature, as evidenced by the many contributions on his reception (Kraemer 1956; Hamori 1978; Kreutz 2004; ʿAtmān 2008). As for the modern literature, Avino (2002) reports the debate on the reception of Greek culture during the nahḍah, with some references to the first translations of Greek literary works into Arabic. ʿAbd al-Ḥayy (1977) explored the reception of Greek myths in the Arabic poetry produced in the first half of the 20th century. Ruocco (2010) provides evidence of a modern dramatic production of Greek derivation. Pormann (2006) observes the reception of the Greek classics by the Lebanese Sulaymān al-Bustānī and the Egyptian Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm and Ṭāhā Ḥusayn. There are also a few studies dealing with the reception of ancient mythology by Arab poets, with a particular interest in the reception of the Mesopotamian myth of Tammuz in the 1950s-1960s (Dāwud 1975; Ḥallāwī 1994; Jayyusi 1977: 720-747).

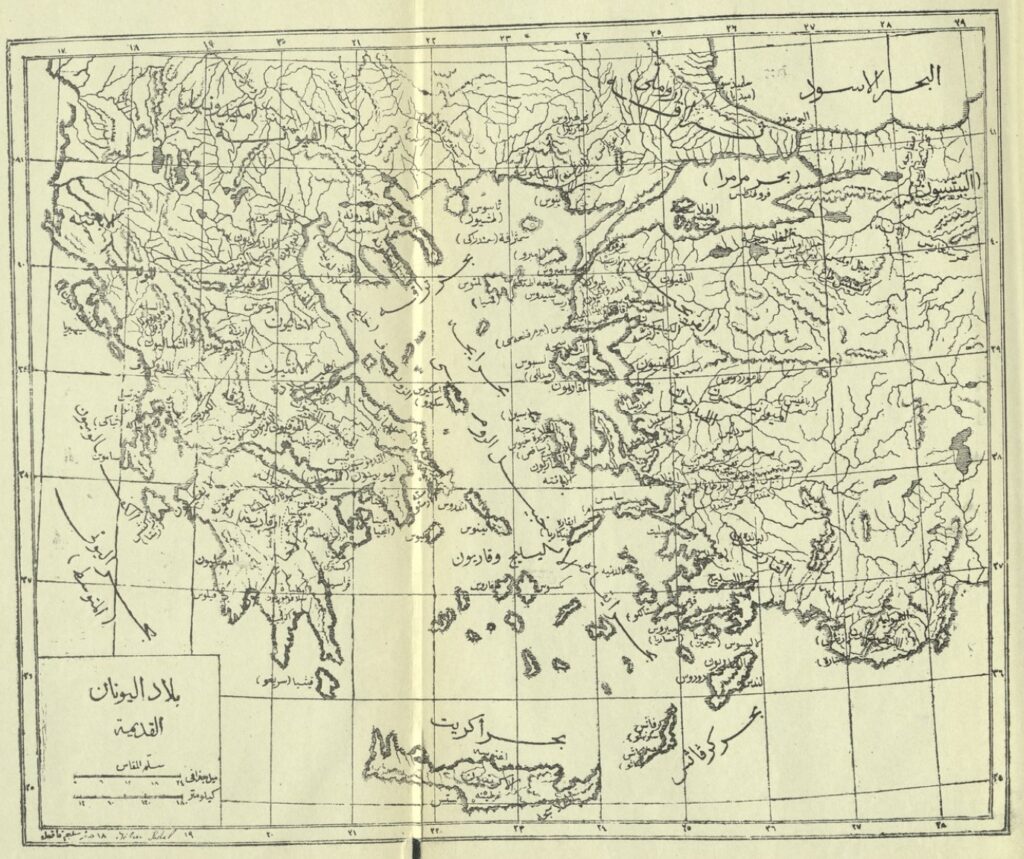

Salīm Fāḍil, Bilād al-Yūnān al-qadīmah (Ancient Greece), in Ilyāḏat Hūmīrūs muʿarrabah naẓman wa-ʿalayhā šarḥ tārīḫī adabī wa-hiya muṣaddarah bi-Muqaddimah fī Hūmīrūs wa-šiʿrihi wa-ādāb al-Yūnān wa-l-ʿArab wa-muḏayyalah bi-muʿǧam ʿām wa-fahāris. Bi-qalam Sulaymān al-Bustānī. [al-Qāhirah], al-Hilāl, 1904.

However, all these studies do not address Greek mythology per se and, when they provide some references to it, they focus on the most mature phase of this reception, that is after the 1940s, when such myths had already been incorporated into the complex heritage that served as a source for Arabic literary creation. They therefore do not explain how, when, why, and which Greek myths made their way into Arabic literature, which one of the many meanings of the myth is conveyed by each text (Leghissa, Manera 2020), and which is the impact of the extra-textual world on the re-configurations of the myths in each rewriting (Heidemann 2003). In other words, they do not explain the process of building what Yaseen Noorani (2019: 252) calls the “shared framework that […] allowed Greek poetic works to have prestige and meaning for Arabic readers”. According to Etman (2008: 18-19), it was precisely the absence of this framework that led to a failure in the understanding of the function of the myth in literature, and consequently to the neglect of the translation of works like the Iliad in the Middle Ages.

DIGIMYTH aims to explore the understudied period before 1950 and expand the corpus beyond the limits of poetry and canonical texts (Snir 2017). As for the temporal framework of the project, DIGIMYTH has limited its research to the years ranging from 1850 to 1950 ca, that is to the period between the appearance of the first references to Greek mythology up to the political and cultural turning point of 1948 (nakbah). Inevitably, this temporal limit has led to a spatial one, because over the years taken into consideration the leading areas in cultural development were Egypt and the Mashreq. With regard to the nature of the corpus, it is certainly true that poetry was one of the most receptive fields for Greek myths, but it is also true that those penetrated even at an earlier stage through other channels and genres. This is why the project considers not only poetry before 1950, but also: lectures; translations; essays; encyclopaedic lemmas; journal articles; drama; school and university curricula.

The general objectives of DIGIMYTH are to investigate how, when and which Greek myths were introduced into modern Arabic literature and to evaluate their impact on its development. The project envisages two primary specific objective:

- The identification of modern Arabic literary texts containing references to Greek myths. This entails the collection and cataloguing of these texts in a database and after that the digitization, encoding and annotation of relevant key texts related to Greek myths, which will be collected in a digital archive.

- The understanding of the dynamics of the reception of Greek myths in modern Arabic literature. The project will carry out a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the data collected in the database and the archive, resting on a methodology that mixes digital tools with literary, historical and religious studies.

Bibliography

ʿAbbās, I. (1977). Malāmiḥ yūnāniyyah fī l-adab al-ʿarabī. Bayrūt, al-Muʾassasah al-ʿarabiyyah li-l-dirāsāt wa-l-našr.

ʿAbd al-Ḥayy, M. (1977). al-Usṭūrah al-iġrīqiyyah fī ʾl-šiʿr al-ʿarabī al-muʿāṣir (1900-1950). Dirāsah fī ʾl-adab al-muqāran, al-Qāhirah, Dār al-nahḍah al-ʿarabiyyah.

ʿAtmān (Etman), A. (2008). “Muqaddimat al-ṭabʿah al-ūlà”. In: Hūmīrūs. al-Ilyāḏah. Ed. A. ʿAtmān. al-Qāhirah, al-Markaz al-qawmī li-l-tarǧamah, p. 18-113.

Avino, M. (2002). L’Occidente nella cultura araba dal 1876 al 1935. Roma, Jouvence.

Bernal, M. (1987). Black Athena. The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization. Volume I: The Fabrication of Ancient Greece 1785-1985. New Brunswick (NJ), Rutgers University Press.

Capezzone, L. (1998). “La politica ecumenica califfale: pluriconfessionalismo, dispute interreligiose e trasmissione del patrimonio greco nei secoli VII-IX”. Oriente Moderno 78, 1, p. 1-62.

Casanova, P. (2004). The World Republic of Letters. Cambridge-London, Harvard University Press.

Dallmayr, F. (1996). Beyond Orientalism. Essays on Cross-Cultural Encounter. Albany, State University of New York.

Dāwud, A. (1975). al-Usṭūrah fī l-šiʿr al-ʿarabī al-ḥadīṯ. al-Qāhirah, Dār al-maʿārif.

Gutas, D. (1998). Greek Thought, Arabic Culture. London-New York, Routledge.

Ḥallāwī, Y. (1994). al-Usṭūrah fī l-šiʿr al-ʿarabī al-muʿāṣir. Bayrūt, Dār al-Ādāb.

Hamori, A. (1978). “Reality and Convention in Book Six of Bustani’s ‘Iliad’”. Journal of Semitic Studies 23, 1 (Spring), p. 95-101.

Heidmann, U. (Ed.) (2003). Poétiques comparées des mythes: de l’antiquité à la modernité. Lausanne, Payot.

Jayyusi, S.K. (1977). Trends and Movements in Modern Arabic Literature. Leiden, Brill.

Kraemer, J. (1956). “Arabische Homerverse”. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 106, 2, p. 259-316.

Kreutz, M. (2004). “Sulaymān al-Bustānīs Arabische Ilias: Ein Beispiel für arabischen Philhellenismus im ausgehenden Osmanischen Reich”. Die Welt des Islams 44, 2, p. 155-194.

Leghissa, G.; Manera, E. (2020). Filosofie del mito nel Novecento. Roma, Carocci.

Noorani, Y. (2019). “Translating World Literature into Arabic and Arabic into World Literature: Sulayman al-Bustani’s al-Ilyadha and Ruhi al-Khalidi’s Arabic Rendition of Victor Hugo”. In: Booth, M. Migrating Texts. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press.

Pormann, P. (2006). “The Arab ‘Cultural Awakening (Nahḍa), 1870-1950, and the Classical Tradition”. International Journal of the Classical Tradition 13, 1 (Summer), p. 3-20.

Rosenthal, F. (1992). The Classical Heritage in Islam. Transl. by E. and J. Marmorstein. London-New York, Routledge.

Ruocco, M. (2010). Storia del teatro arabo. Dalla nahḍah a oggi. Roma, Carocci.

Snir, R. (2017). Modern Arabic Literature. A Theoretical Framework. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press.

Strohmeier, G. (2003). Hellas im Islam. Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz.